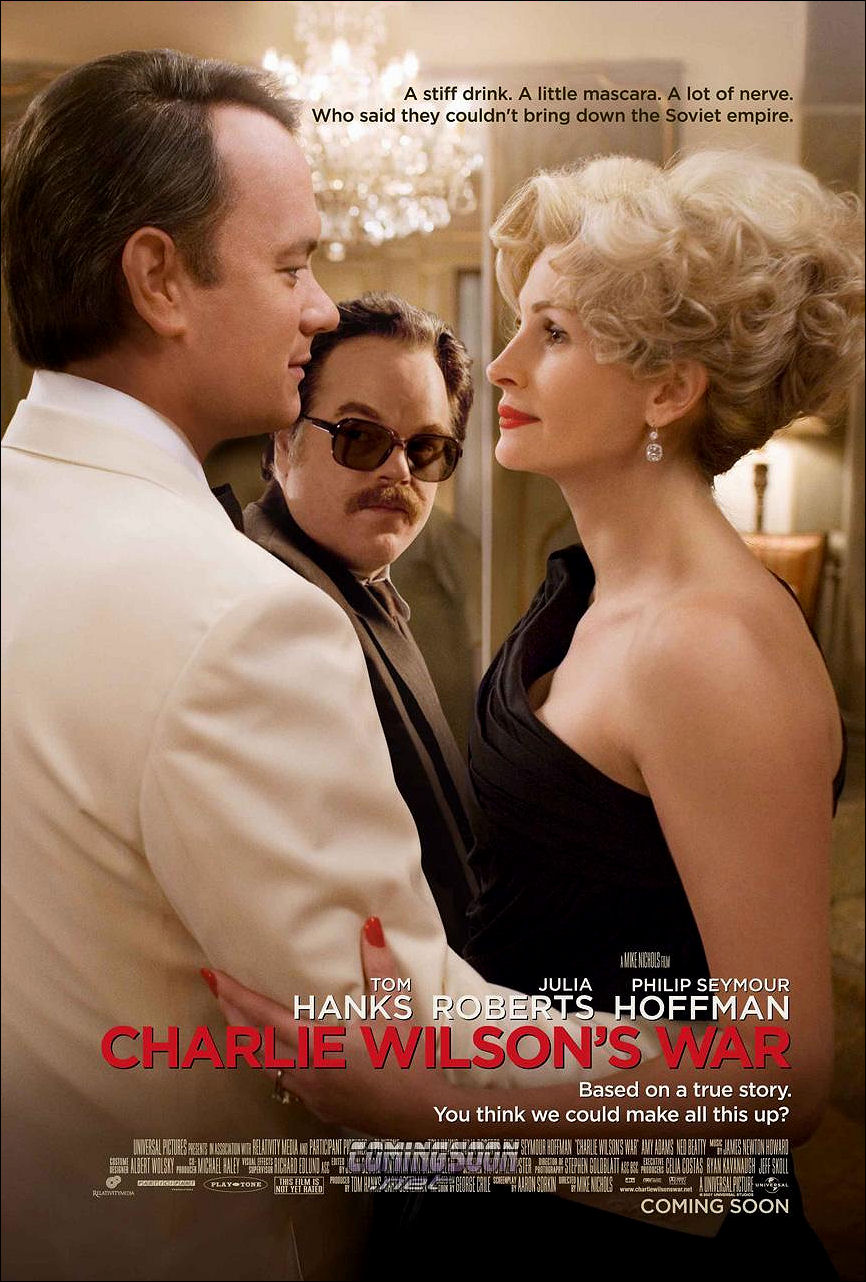

I watched Charlie Wilson's War last night--and thoroughly enjoyed it, though not for the reasons one would imagine. It heralds the work of Congressman Charlie Wilson of Texas in the 1980s (played by Tom Hanks) who managed to arm the Afghans in their successful struggle against the Soviet Union and concludes with a rather simplistic warning that the US fought a great covert war at the outset but seriously "messed-up" the endgame (the director chose a much more descriptive phrase).

I watched Charlie Wilson's War last night--and thoroughly enjoyed it, though not for the reasons one would imagine. It heralds the work of Congressman Charlie Wilson of Texas in the 1980s (played by Tom Hanks) who managed to arm the Afghans in their successful struggle against the Soviet Union and concludes with a rather simplistic warning that the US fought a great covert war at the outset but seriously "messed-up" the endgame (the director chose a much more descriptive phrase).What intrigued me was a little Taoist and/or Zen story that CIA rogue Gus Avrokotos (played by Philip Seymour Hoffman) relates at the end of the film. Wilson is ready to celebrate the Afghan victory made possible by covert US assistance. Avrokotos gives him cause for pause with this story (mutilated by Hollywood, of course; I offer a truer version here) about a farmer whose horse ran away.

When his neighbors heard the news, they ran over to see him. "What terrible luck," they said.

The farmer was non-plussed. "We'll see," he replied.

The next morning the horse returned, bringing with it three other wild horses.

"This is great news," his neighbors said excitedly.

"We'll see," replied the old man.

The following day, his son tried to tame one of the wild horses and was thrown off and broke his arm.

The neighbors again offered their sympathy.

"We'll see," said the farmer.

The very next day the army came through, drafting young men to fight for the emperor. The son couldn't serve because his leg was broken.

The neighbors congratulated the farmer on his good luck.

"We'll see" said the farmer.

Avrokotos was right, as it turned out. What seemed good at the moment wouldn't turn out so well in the end.

Why is it that what I think is good for me can easily turn out to be bad? And what I celebrate as good can turn out to be terribly destructive? The truth of the matter is that goodness and badness do not reside in the events of our lives but rather within ourselves--in the meaning (or lack thereof) that you and I bring to the events that happen to us. In this sense, we are determiners of our own fates. We bring meaning along with us. It resides within, where the heart is.

I remember sitting on the edge of a bed in a leper colony in the Philippines when I was a middle schooler. My mother and I were visiting a friend who was a pastor and a leper and who lived in debilitating poverty. She asked him, "What do you do when you don't have any food to eat?" He replied, "I just mix a little sugar with water and praise the Lord."

Could I ever say such a thing in a similar circumstance?

We'll see.

2 comments:

The 'We'll see...' narrative was definitely meaningful in the movie. I was also stirred by the idea that a clear vision (in this case, shooting down helicopters) can be so effective when singularly pursued without regard to the conventional 'wisdom' of the systems at work.

The plight of the refugees was a reminder of the impoverished worldwide. Recent TV images of the shantytown Kenyans in post-election revolt come to mind now.

Maybe a clearer vision will be part of what 'we'll see' in the new year. Blogging in hope, Tom

Good point about the plight of refugees, Tom. I notice that some reviewers have been critical of the films "minimalist" approach to the refugee camp. It struck me that the film depicted refugees in exactly the same way that many tourists experience a refugee camp when traveling abroad. You pass through in a van or car, look over the scene, and then move on. I think we need to keep in mind that this is a truly surface kind of immersion.

Post a Comment